Weight loss is big business in America — over a $60 billion annually.[2] This is no surprise when you consider that one in three Americans over the age of 20 is considered obese, and over 70% of the population is classified as overweight.[3]

The Biggest Loser woos people with magical weight loss transformations, but a new study shows the methods employed by the shows leave the contestants worse off than where they started. Image courtesy Wikimedia

Nutrition and media companies alike are well aware of this, and each year there are new products and TV series dedicated to “rapid transformations” and “stunning results.” One of the first of these television programs was The Biggest Loser. Each season obese and overweight contestants went on a grueling multi-month competition to see who could lose the most amount of weight in the least amount of time.

Participants followed a rigorous exercise regimen and extreme diet program in order to obtain those eye-popping transformations plastered all over the TV screen and print ads.

While everything seems great for these individuals at the conclusion of the program, a new study has shined some light on the long term effects of extreme dieting.

The Study

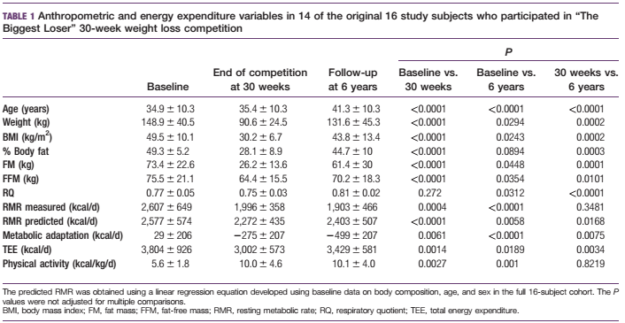

A group of researchers (who have previously investigated metabolic adaptations following extreme weight loss[4]) sought to measure long-term changes in resting metabolic rate (RMR) and overall body composition in participants of The Biggest Loser.[1]

To see if any lasting damage was done from the contest, researchers recruited 14 of the 16 original members of The Biggest Loser Season 8. RMR and body composition changes were taken 6 years after the end of the weight loss competition.

To do this, they used dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and measured RMR by indirect calorimetry at baseline — comparing the end of the 30-week competition and that of 6 years later. Metabolic adaptation was defined as the residual RMR after adjusting for changes in body composition and age.

The Results

14 of the original 16 cast members on The Biggest Loser participated in the follow-up study. When the competition ended, members lost on average 128 lbs (58.3kg) and their Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) was decreased by an average of 610 calories.

In the six years since the original members completed the competition, contestants regained 90lbs (41kg) on average, and their resting metabolisms have further decreased to an average of 704 calories below their original baseline values at the start of the competition!

Researchers found that 6 years following the competition, contestants regained a majority of their weight, and their resting metabolic rates were WORSE than when they were on the show…

The study also showed that contestants’ bodies produce less leptin, the hormone that helps regulate hunger levels in the body. This has led to contestants having to work even harder to refrain from eating someone of the same size – a theory we discuss in our analysis of the new show, Fit to Fat to Fit.

What Does this mean?

Basically, when the series started, contestants had a normal metabolism for someone overweight, i.e. they burned a normal number of calories each day. However, following the extreme diet and exercise protocol employed on the show, contestants’ metabolisms had drastically slowed down and their bodies simply aren’t burning enough calories to maintain their slimmer physiques.

To put some numbers to this, at the beginning of the competition, contestants had an average RMR of 2,607 ± 649 kcal/day. At the conclusion of the 30-week contest, competitors were left with a metabolism of 1,996 ± 358 kcal/day at the end. This is what extreme caloric restriction does to you. But six years later, they gained weight back and their metabolisms were even lower at 1,903 ± 466 kcal/day.

Ultimately, the researchers concluded that, “those subjects maintaining greater weight loss at 6 years also experienced greater concurrent metabolic slowing.”

Sure, our metabolisms will slow after six years of aging, but not that much! Effectively, this TV show put contestants’ bodies into “starvation mode” and literally screwed them up – possibly permanently!

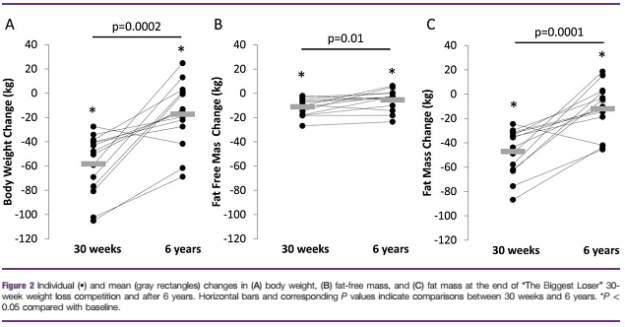

This graph illustrates what we’ve been saying. 6 years after appearing on the show, individuals were all in worse health and gained back more fat than when they finished the show.[1]

This is not how you do it

A goal of dieting is to lose weight while eating as much as you can in order to achieve fat loss. This is done by choosing high-protein, nutrient-dense, and mineral-dense foods. When doing this, you appropriately tackle appetite (and its underlying hormones), and then can more effortlessly put burn fat.

The problem with extreme measures and crash diets such as seen in The Biggest Loser are that they focus solely on how much weight you can lose and how fast you can lose it. Therein lies the problem: America’s obsession with immediacy of results!

This study shows that improperly employing crash diets and extreme exercise protocols wrecks your metabolism (along with various other hormonal systems) and can ultimately leave you in a worse place than where you began your weight loss journey.

DISCIPLINE, not Motivation

Forget motivation. It won’t last anyway. Get disciplined and make this a part of your everyday life. Image courtesy BloggingWithJazz

As with all great things in life, health comes down to sheer discipline, not motivation.

Motivation is fun, but motivation fades. Motivation leads to dumb ideas like crash dieting.

Go follow a healthy person around, or a successful businessperson. Their motivation may go up and down with time, but their discipline never fades. They never stop working out. They never stop eating right (and they know what “eating right” means). They never stop reading and getting better. It is just simply part of their lives.

In fact, you might be better off removing the word “motivation” from your entire vocabulary. You don’t need it. You need discipline.

If this study teaches us anything, it’s that we need to stop looking for the quickest and easiest way out in life and if you want results, you have to commit to a plan, pace yourself, and STAY DISCIPLINED, year in and year out!

References

- Fothergill, E., Guo, J., Howard, L., Kerns, J. C., Knuth, N. D., Brychta, R., Chen, K. Y., Skarulis, M. C., Walter, M., Walter, P. J. and Hall, K. D. (2016), Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity. doi: 10.1002/oby.21538

- http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-us-weight-loss-market-2014-status-report–forecast-246304741.html

- http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/Pages/overweight-obesity-statistics.aspx

- Johanssen DL, Knuth ND, Huizenga R, Rood J, Ravussin E, Hall KD. Metabolic slowing with massive weight loss despite preservation of fat-free mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:2489–2496.