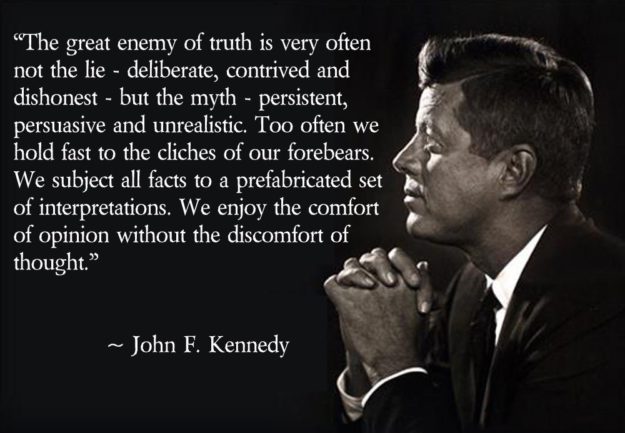

"The great enemy of truth is very often not the lie - deliberate, contrived, and dishonest - but the myth - persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic. Too often we hold fast to the cliches of our forebears. We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought."

-- John F. Kennedy[1]

The Enemy of Truth is not necessarily the lie, but the myth. Today, we fight to destroy one such myth.

Sometimes, no matter how much data you throw at a lie, it just won't die. That lie is the total myth that "high protein consumption is bad for the kidneys".

So what does the scientific community do to that myth? Bury it, and bury it deep.

And that's exactly what Dr. Stuart M Phillips and his stellar team of researchers did, after publishing a meta-analysis that included 28 studies with over 1,300 participants. After compiling and analyzing the data, we have a clear verdict on what the research says:

High Protein Diets do NOT Damage Healthy Kidneys!

You can check out the open access meta-analysis yourself,[2] but if that's a bit too complicated and long-winded, we've put together a simpler breakdown here (as well as a video below), with the essentials of the study.

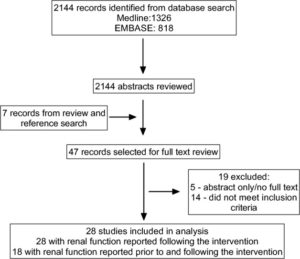

Selecting qualifying studies

A meta analysis is only as good as the studies it utilizes. In order to get appropriate studies, the researchers were only interested in studies that compared "high protein diets" to "lower protein diets". In this context,

Definition: "High protein diets" ("HP" group)

- ≥ 1.5 g protein per kg body weight (≥ 0.68 g/lb)

- ≥ 20% energy intake, or

- ≥ 100 g protein/day

Definition: "Normal" or "Lower protein diets" ("NLP" Group)

- ≥ 5% less energy intake from protein per day compared with the high protein group

A study was only considered if it

- used randomized controlled trials,

- compared high protein to moderate or low protein diets,

- measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and

- was not an acute (one meal) or short-term study (three days or less).

All others were excluded, leaving 28 studies total.

What is Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)?

Glomerular filtration is the first step in the production of urine, and Glomuerular Filtration Rate (GFR) is the volume of fluid that gets filtered to the second step in a given amount of time. On average, humans filter 125mL per minute or 180L per day. The biological process is quite complex, and if you're interested, there are fantastic videos on YouTube diagramming it from start to finish.

The reason we care is because GFR is simply a way to test how well the kidneys are working.[3] There is a healthy GFR range, with rates too low being the most common diagnosis of kidney problems, but rates that are too high could also indicate issues.

Phillips and team used GFR because it's actually used as a reason to discourage high protein diets. The theory that protein affects kidney function is because there's increased renal solute load (as urea), which could eventually lead to glomerular damage, kidney damage, and ultimately failure. Urea is a nitrogenous compound that your kidneys need to filter, and the original thinking was that all of this urea filtration may eventually lead to kidney failure.

While this might be true for those with compromised kidney function, it's simply not playing out that way, and recent investigations have shown no added benefits to low protein diets in such patients,[4] leading many to question if protein is truly the problem in the first place.

Back to the meta analysis at hand: Surely, if these diets were causal for kidney damage, they'd show up in GFR, which has been the cornerstone of the protein kidney damage myth.

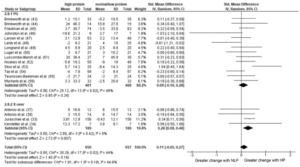

The results? High Protein Diets do NOT Cause Kidney Damage!

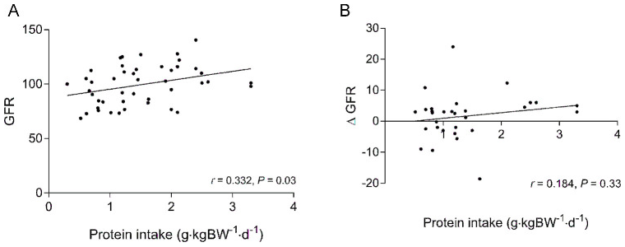

So what exactly was the final verdict? Simple: Dietary protein has no effect on GFR rate, and as such, high protein diets do not negatively impact the kidneys.[2]

The long and short of it is that those with high protein diets had higher GFRs at the end.

The data shows a dose-response effect between increasing protein intake and post eGFR! The myth is not only wrong, it's completely wrong![2]

While some may hypothesize that those consuming higher protein diets are generally living healthier and more active lifestyles, the data points to universally better kidney function, and we're honestly most concerned with those attempting to live said healthy/active lifestyles in the first place.

A few of the key studies analyzed

Each study is interesting on its own, but when all 28 are collected, the data is overwhelming. Here are some snippets:

- Jose Antonio and team conducted two crossover studies on athletic men with the highest protein intakes analyze (3.3g/kg vs 2.5-2.6g/kg), and both showed GFRs increasing.[5,6] The subjects added whey protein and ate ad libitum (as much as they wanted).

- Wycherly, et al performed a diet comparison study in Australia looking at high-protein diets against high-carbohydrate diets.[7] Creatinine clearance improved in the high-protein diet but slightly worsened in the high-carb diet. The high-protein diet lost more weight, burned more fat, and kept more muscle.

- Roughead et al performed a four week study exclusively on postmenopausal women, noting that a high-meat diet had higher GFR than a diet based upon vegetable protein, and did not affect urinary calcium loss or indicators of bone metabolism.[8]

- Skov et al compared low-fat diets that were high-protein and low-protein. The high protein diet's GFR improved, while the low-protein diet's GFR declined.[9]

The list goes on. It doesn't matter if it's with male athletes, young women, menopausal women, or a mixed demographic. High-protein diets aren't only safe for kidneys, they seem protective! Kidney function is nearly universally worse on a low protein diet, and better on a high protein diet.

We have mountains of data affirming this, statistically significant and well-constructed. No matter which way you look at it, the protein-kidney-myth is simply that: a myth. And given the gravity of our obesity crisis, the disinformation from the mainstream media needs to end right immediately.

Improving upon past meta analyses

This study wasn't the first time arriving at such a conclusion, but it's definitely the best.

Robert Morton (left) and Stuart Phillips (right) have put together a fantastic meta-analysis to disprove the "protein-kidney-damage" myth!

A 2014 meta-analysis from researchers Schwingshackl and Hoffman also showed that high protein diets have higher GFRs (again, that means better kidney function) in subjects with normal functioning kidneys.[10] These researchers used 30 studies with over 2000 subjects, and they also came to the conclusion that a higher protein intake is associated with a higher GFR.

So why the new meta analysis by Dr. Phillips and team? Unfortunately, Dr. Phillips saw a major flaw in the conclusions drawn: only total GFR after the trials was measured, not the change in GFR, which is what we should be looking at.

Only looking at the post-trial GFR data will tell us simply how well the kidneys are working after the trial. That doesn't necessarily account for how well they were working before the trial. Since this adds potential holes in a study (such as GFR went from "great" to "good"), Phillips centered his meta-analysis around the difference between pre- and post-trial GFR data.

Schwingshackl and Hoffman: The most nonsensical conclusion ever written?

After seeing high-protein diets associated with higher GFR but also higher serum urea, urinary calcium excretion, and serum concentrations of uric acid, Schwingshackl and Hoffman then concluded with one of the most irresponsible things ever written on the topic of obesity:

"In the light of the high risk of kidney disease among obese, weight reduction programs recommending HP diets especially from animal sources should be handled with caution."

-- Schwingshackl and Hoffman, 2014

This "caution" couldn't be further from the truth! Had they understood the thermic effect of protein, the fact that it has the highest satiety,[11] and "Protein Leverage",[12] they would know that low protein diets are what should not only be handled with caution, but completely avoided.

Prioritize Protein!

The Protein Leverage Hypothesis effectively states that animals (including humans) prioritize protein, and will easily overcompensate in fats and carbs in order to get adequate amounts. Long story short, your body will get that protein in, whether it comes from a steak or two tubs of ice cream. This is why you leverage protein by prioritizing it in every meal - a subject for a future article.

Fear-mongering over serum urea levels, which healthy kidneys have no problems with, is the exact wrong thing to recommend to an obese person whose body nearly only needs protein, as they have plenty of energy on hand.

Needless to say, Phillips and team knew that the community desperately needed a more well-constructed, better-written meta-analysis.

The benefits of high protein diets

Higher protein diets, as compared with the RDA, have several benefits. Here's a quick overview of some of the benefits learned from the studies that this meta analysis includes:

- Greater amounts of muscle hypertrophy for individuals weight training[13]

- Increases weight lost during diets, while maintaining lean muscle mass[14,15]

- Mitigating the effects of sarcopenia[16,17]

- Increased satiety, lowering daily energy intake[9]

In fact, those with chronic kidney disease can benefit from a higher protein diet,[18,19] showing no added damage in certain types of kidney disease and going against what was originally hypothesized. So, for those with undamaged kidneys, there shouldn’t be any sort of issue with our filtration of the urea byproduct.

Conclusion: This kidney myth needs to die. Protein is beneficial.

Dr. Phillips and team performed the best meta analysis to date on this topic, and there's been such an abundant amount of data to back it up that the debate has now been put to rest.

Humans are well-adapted for not only intermittent fasting, but "intermittent feasting". We can eat and utilize high amounts of protein, and the best and most abundant source for that is fish and animal-based proteins. Our bodies prioritize this protein intake, going to potentially insane lengths to get adequate amounts.

When we feast on said protein, does urea byproduct increase? Of course. Does that damage our kidney function, though? No, it does not. This is exactly what the kidney is adapted to do.

For the near entirety of the population, we can safely say that the benefits of high protein diets are vast, and that the myth of your whey protein shake shutting down your kidneys is officially busted.

References

- John F Kennedy; "Commencement Address at Yale University"; New Haven, Connecticut; June 11, 1962; https://jfkl.prod.acquia-sites.com/asset-viewer/archives/JFKWHA/1962/JFKWHA-104/JFKWHA-104

- Devries MC, Sithamparapillai A, Brimble KS, Banfield L, Morton RW, Phillips SM; "Changes in Kidney Function Do Not Differ between Healthy Adults Consuming Higher- Compared with Lower- or Normal-Protein Diets: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis"; Journal of Nutrition; vol. 148,11 (2018): 1760-1775; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6236074/

- Levey, Andrew S et al; "Glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for detection and staging of acute and chronic kidney disease in adults: a systematic review"; JAMA vol. 313,8 (2015): 837-46; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410363/

- Fouque D, Laville M; "Low protein diets for chronic kidney disease in non diabetic adults"; The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Jul 8, 2009; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19588328

- Antonio, Jose et al. "The effects of a high protein diet on indices of health and body composition--a crossover trial in resistance-trained men" Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition vol. 13 3. 16 Jan. 2016; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4715299/

- Antonio, Jose, et al; "A High Protein Diet Has No Harmful Effects: A One-Year Crossover Study in Resistance-Trained Males"; Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism; Volume 2016, Article ID 9104792, 5 pages; https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jnme/2016/9104792/

- Wycherley, T P et al; "Comparison of the effects of 52 weeks weight loss with either a high-protein or high-carbohydrate diet on body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight and obese males"; Nutrition & diabetes vol. 2,8 e40. 13 Aug. 2012, doi:10.1038/nutd.2012.11; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3432181/

- Roughead, Z, et al; "Controlled high meat diets do not affect calcium retention or indices of bone status in healthy postmenopausal women"; Journal of Nutrition; 133(4):1020-6; April 2003; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12672913

- Skov A, Toubro S, Ronn B, Holm L, Astrup A. Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999;23(5):528–36; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10375057

- Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Comparison of high vs. normal/low protein diets on renal function in subjects without chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014;9(5):e97656; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4031217/

- Paddon-Jones, D, et al; "Protein, weight management, and satiety"; American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; 87(5):1558S-1561S; May 2008; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18469287

- Simpson S, Raubenheimer, D; "Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis"; Obesity Reviews; 6(2):133-42; May 2005; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15836464 (Archive)

- Cermak N, Res P, de Groot L, Saris H, van Loon L. Protein supplementation augments the adaptive response of skeletal muscle to resistance-type exercise training: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:1454–64; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23134885

- Wycherley T, Moran L, Clifton P, Noakes M, Brinkworth G. Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96(6):1281–98; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3432181/

- Josse A, Atkinson S, Tarnopolsky M, Phillips S. "Increased consumption of dairy foods and protein during diet- and exercise-induced weight loss promotes fat mass loss and lean mass gain in overweight and obese premenopausal women." J Nutr 2011;141(9):1626–34; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3159052/

- Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, Cesari M, Cruz-Jentoft A, Morley J, Phillips S, Sieber C, Stehle P, Teta D et al. Evidence-based recommendation for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(8):542–59; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23867520

- Deutz N, Bauer J, Barazzoni R, Biolo G, Boirie Y, Bosy-Westphal A, Cederholm T, Cruz-Jentoft A, Krznariç Z, Nair K et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clin Nutr 2014;33(6):929–36; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24814383

- Joint WHO/FAO/UN University Expert Consultation Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2007;935:1–265; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18330140

- National Kidney Foundation; "Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)"; CKD Work Group KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013;3:1–150; https://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/CKD/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf